Published on

February 10, 2026

~

8

min

What does a “successful” 90-day digital commerce launch really cost you?

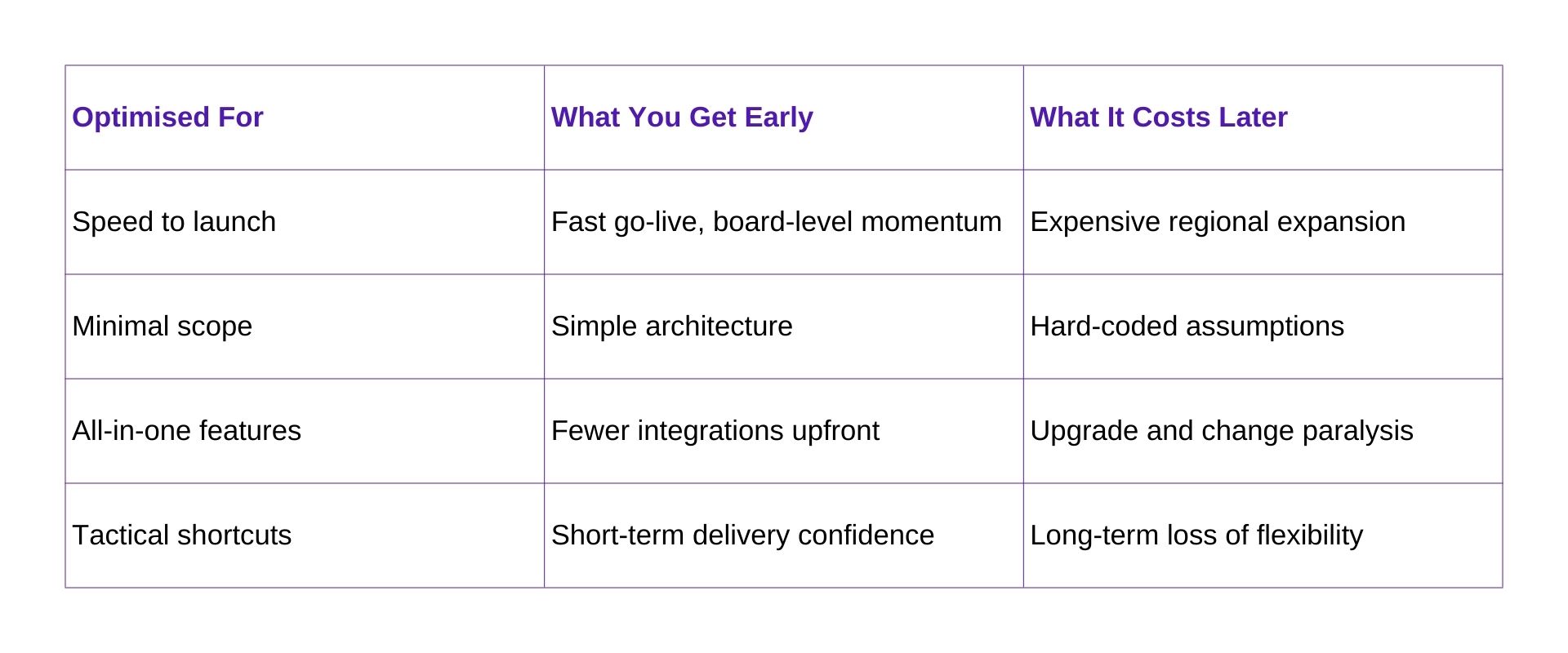

In enterprise commerce, the most expensive projects aren’t the ones that stall. They’re the ones that launch fast and quietly limit every decision that follows.

Quick wins don’t disappear after go-live. They harden into architecture, operating models, and assumptions about how the business works. What looks like speed in a board deck often locks in single-region logic, simplistic catalogues, brittle pricing, and fragile integrations.

The result feels like momentum at first. Over time, it shows up as slower change, higher risk, and rising cost for even modest improvements.

This is the hidden trade-off behind “quick wins” in enterprise digital commerce and why launch speed alone is a poor measure of progress.

In digital commerce, a “90-day win” prioritises launch speed over long-term scalability. It delivers fast visibility, then quietly restricts what comes next: new regions, channels, pricing models, and customer experiences. The short-term gain is momentum. The long-term cost is structural drag.

Early launches often optimise for one market, one catalogue, and minimal integrations.

That approach works…Until the business tries to expand! What looks like a simple next step quickly turns into rework, because early assumptions are embedded deep in the architecture.

Shortcuts taken for speed don’t disappear after go-live. They compound.

The result is predictable: delivery slows, risk increases, and budgets shift from innovation to cleanup. The platform didn’t fail. It succeeded at doing exactly what it was designed to do, support yesterday’s business model.

A real digital commerce win isn’t defined by how fast you launch. It’s defined by how cheaply and safely you can change after launch, quarter after quarter, market after market.

Enterprise commerce architecture defines how product, pricing, customer, and order systems are modelled and connected so the business can change safely and predictably.

When short-term velocity becomes the primary metric, architectural risk rises, and release velocity inevitably collapses as systems grow.

Most “launch-first” programs exhibit the same structural weaknesses,

In healthy delivery practices, organisations aim for high deployment frequency and low lead times for change, which are proven indicators of adaptive architecture and delivery performance.

Enterprises with modular, decoupled systems consistently achieve faster, safer releases and stronger quality outcomes, while monolithic or tightly coupled systems are slow to release monthly or less, increasing regression risk and delivery overhead.⁴

Right after launch, teams often maintain high velocity. Tuning UX, fixing edge cases, and patching minor bugs.

But as requirements expand, even small changes ripple across dependent systems: a new payment provider touches checkout, fraud, OMS, CRM, and compliance; a pricing tweak spans front end, promotions, reporting, and back end. Each release pulls more stakeholders into planning and expands QA cycles, slowing release cadence.

This is the moment where early architecture choices collide with bigger ambitions.

Teams aren’t losing talent; the architecture is blocking progress. What felt like momentum at launch becomes structural drag, because without a clear separation of domains, every change carries high cross-system risk.

An all-in-one commerce platform bundles capabilities like search, CMS, cart, promotions, and order management into one vendor product. It simplifies procurement and early delivery. Over time, it often trades flexibility for convenience.

In year one, it feels efficient. You configure instead of integrate. You accept default flows. You shape your process around the platform.

Then the business moves faster than the vendor roadmap.

Marketing wants loyalty mechanics the native engine can’t express. B2B teams need account hierarchies and contract pricing. You need mobile-first or partner experiences that reuse commerce logic without inheriting the full front end.

So you customise. Plugins pile up.

Over time, the pattern repeats:

That’s when the all-in-one vs. composable tradeoff becomes real. All-in-one moves faster upfront. Composable starts slower, but it keeps absorbing change. Three years in, an over-customised all-in-one stack resists change. A well-designed composable setup keeps moving.

The “simple” early choice narrows your options later. Quietly. Relentlessly.

Customer experience in digital commerce is the full journey, discovery, buying, service across channels. And it reflects your data quality, your integrations, and your architecture, whether you want it to or not.

When shortcuts run through pricing, inventory, and promotions, customers feel the impact immediately:

When data stays fragmented across ERP, CRM, PIM, and the commerce engine, personalisation stalls. Omnichannel plans suffer because stores, distributors, and partners see different pricing and availability than the website. Peak periods expose performance issues, checkout friction, and abandonment.

CX doesn’t degrade by accident. It reflects every architectural compromise you made and forgot to revisit.

The promise of “launch now, improve CX later” rarely shows up in reality. CX becomes the visible symptom of hidden debt.

Designing for change means building digital commerce so adding regions, channels, and business models stays incremental, not a re-platform. It treats architecture, modularity, and data as strategic assets. The win shifts from launch speed to change speed.

So stop asking, “How fast can we launch?” Ask the question that actually protects your roadmap: “How cheaply and safely can we change after we launch?”

That single shift drives better decisions:

Prioritise loose coupling between the front end and core commerce logic. Separate systems of record (ERP, CRM, PIM) from systems of engagement (experience, experimentation, personalisation). Build a data foundation that supports real segmentation and personalisation, not slideware.

You still launch. You just define the win differently.

A real win isn’t a date on a calendar. It’s a platform that gets easier to change over time.

In enterprise digital commerce, a true win is a platform that still lets you move fast in year three and beyond. Measure it by adaptability, resilience, and the cost of your next change, not the time to first launch.

That requires a different executive conversation.

Don’t sell modularity and data foundations as “engineering quality.” Frame them as the difference between a stack that blocks commercial strategy and one that amplifies it. Between a platform locked to today’s model and one that supports tomorrow’s.

If you lead digital commerce, stop accepting “quick wins” that treat architecture as an afterthought. Set a clear expectation: every release must leave the system cheaper to change, not more expensive. Track time to the next change alongside time to launch.

Over the next five years, the winners in digital commerce won’t be the companies that launched fastest. They’ll be the ones who refused to trade their future roadmap for a 90-day headline and built systems ready for whatever the business demands next.

Start your own journey today!